Inflammation: A Problem Worth Managing in Dairy Cows?

As seen in Progressive Dairy

High-producing cows are the result of less stress and less inflammation. Minimize the degree of inflammation by implementing sound management practices.

Inflammation. If you’re a dairy producer, this word likely conjure up images of cows battling metritis post-calving or that have severe lameness due to a foot injury and swelling. Or perhaps it’s the cow making frequent trips back to the sick pen because of recurring mastitis that comes to mind. Regardless, inflammation sounds like something you certainly want less of in your herd – and you are partially correct.

In reality, inflammation is a double-edged sword. On one side, cows need inflammation to occur. It is their immune system’s necessary and natural response to any insult she experiences. Inflammation is how her immune system fights the battle. On the other side, inflammation that is excessive and slow to resolve results in many costly outcomes, including lower dry matter intake (DMI), lower milk production and a greater likelihood of chronic inflammation.

Even healthy cows have inflammation

Our understanding of inflammation in dairy cattle is rapidly expanding. While the acute health events we associate with unhealthy cows are the obvious displays of inflammation in your herd, even the cows we perceive as healthy experience a multitude of inflammatory events over their lactation. The greatest concentration of these events happen from dry-off through the fresh period. According to Dr. Andres Contreras (2017), every time a cow experiences significant tissue changes, inflammation is triggered, resulting in mammary involution at dry-off, parturition, expelling of the placenta and uterine involution.

Adipose tissue mobilization is another source of inflammation during the transition period. Most transition cows experience some degree of negative energy balance because DMI lags milk yield, thus the cow mobilizes body fat or adipose tissue. If the cow transitions well to peak lactation and body condition loss is reduced, adipose tissue inflammation is resolved. However, if the cow experiences a difficult transition period (dystocia, retained placenta, etc.), the loss of adipose tissue is more severe, thus causing greater inflammation which is likely to become chronic.

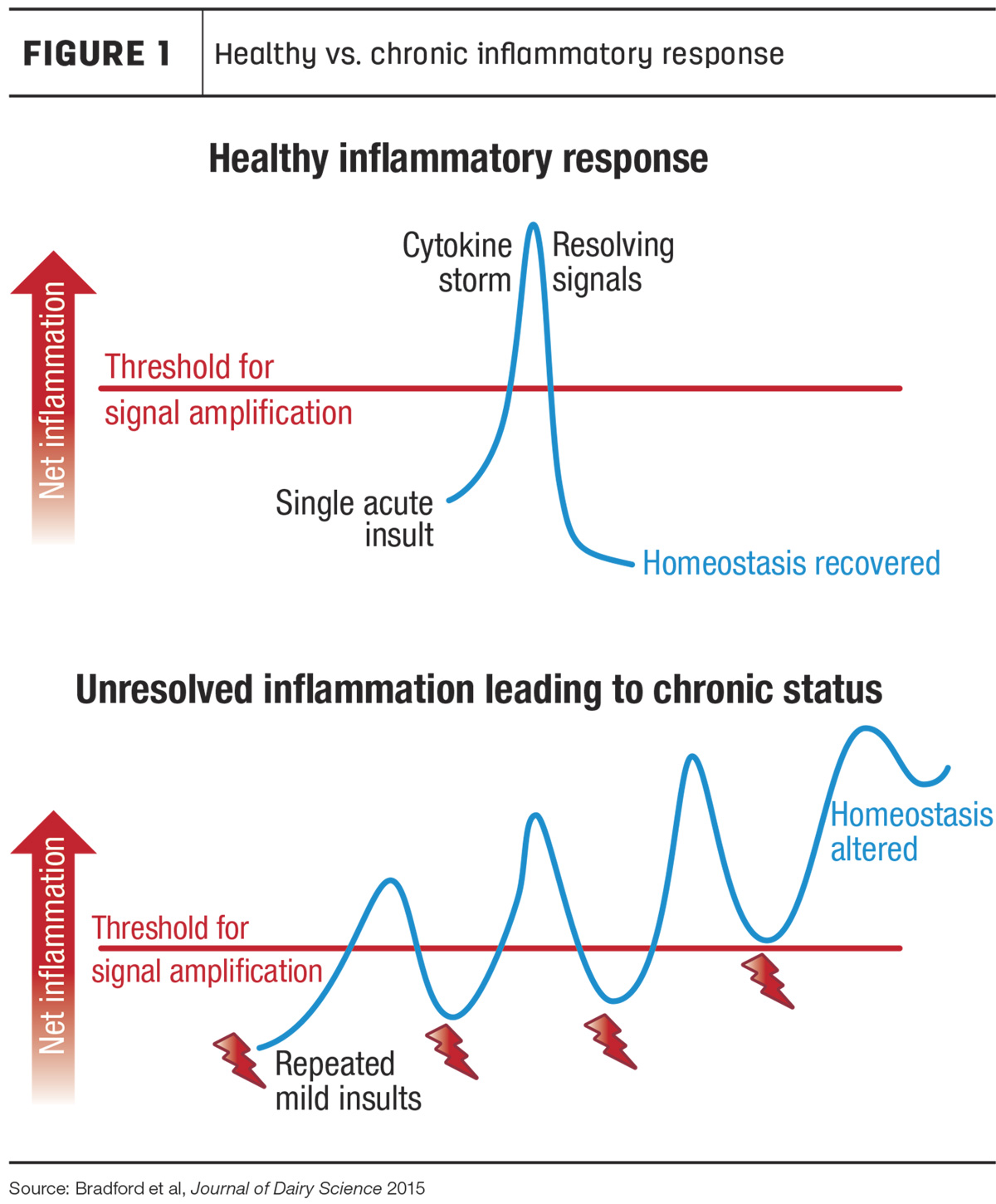

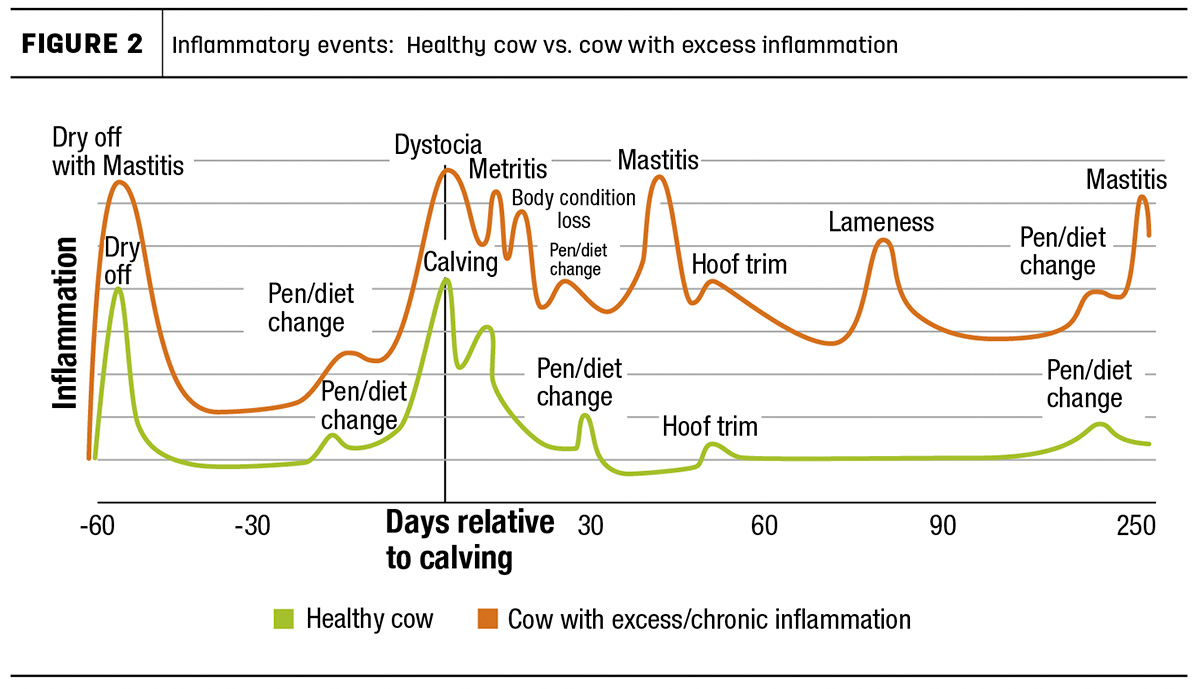

Figure 1 is a summary of metabolic responses to insults in lactating dairy cows. The top graph represents a single acute inflammatory event where inflammation was resolved quickly with little impact on metabolism, while the bottom graph depicts what occurs when a cow has chronic inflammation – the cow never recovers. These mild yet repeated insults cause her baseline inflammation to build, leading to chronic inflammation (Figure 2). The result is often poor lactation performance, reproductive failure and a higher risk of culling. Considering that 25% of the cows that are culled will exit the herd in the first 60 days of lactation, it appears we have too many cows experiencing chronic inflammation.

The tug of war for glucose

The dairy cow undergoes significant metabolic changes from day 250 of gestation to four days postpartum. The demand for glucose triples, there is a doubling of the demand for amino acids, a twofold increase in the flow of blood to the gut and liver, and a fivefold increase in fatty acid requirements. No wonder the transition period is a challenge.

In early lactation, the cows are predisposed to funnel as much glucose as possible to the mammary gland to support milk production. Other tissues like muscle, organs and the nervous system use non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) as their primary fuel source, thus sparing glucose for utilization by the mammary gland. Unfortunately, like the mammary gland, the immune system also requires glucose to function. Therefore, when the immune system is activated due to stress, disease insults or excess adipose mobilization after calving, glucose is now prioritized for the immune response, thus shorting the glucose available for milk production and triggering lost milk yield.

How much glucose can the immune system greedily gobble up? Glucose demand for an acute inflammatory response can use from 0.21 to 0.29 pound of glucose per hour (or 4.4 pounds per day) for a 1,500-pound cow. If we assume a net energy used for lactation (NEL) value of 0.9 Mcal per pound of glucose and it requires 0.34 MCal per pound of milk synthesized, this could support 11.67 pounds of milk per day. High-producing cows clearly have lower inflammation and less glucose demand by their immune system.

Managing for lower inflammation

Given that every cow experiences a multitude of inflammatory events (some more severe than others), what can we due to minimize the degree of inflammation that will occur? Implementing sound management practices should be the first place a producer should start.

- Ensure transition cows are not overcrowded and have 30 to 32 inches of bunk space.

- Maintain proper bedding depth and cleanliness.

- Minimize pen and diet changes.

- Implement proper cooling strategies to reduce heat stress.

- Don’t trim feet or vaccinate the same day you move cows to a different pen.

- Separate primiparous and multiparous cows if possible.

- Reduce time in holding area and parlor to less than one hour per milking.

- Avoid overcrowding pens.

- Feed available 22 to 23 hours per day.

- Provide balanced diets.

- Don’t feed moldy feed.

- Harvest and store forages at correct moisture and density.

Treat or feed for reduced inflammation?

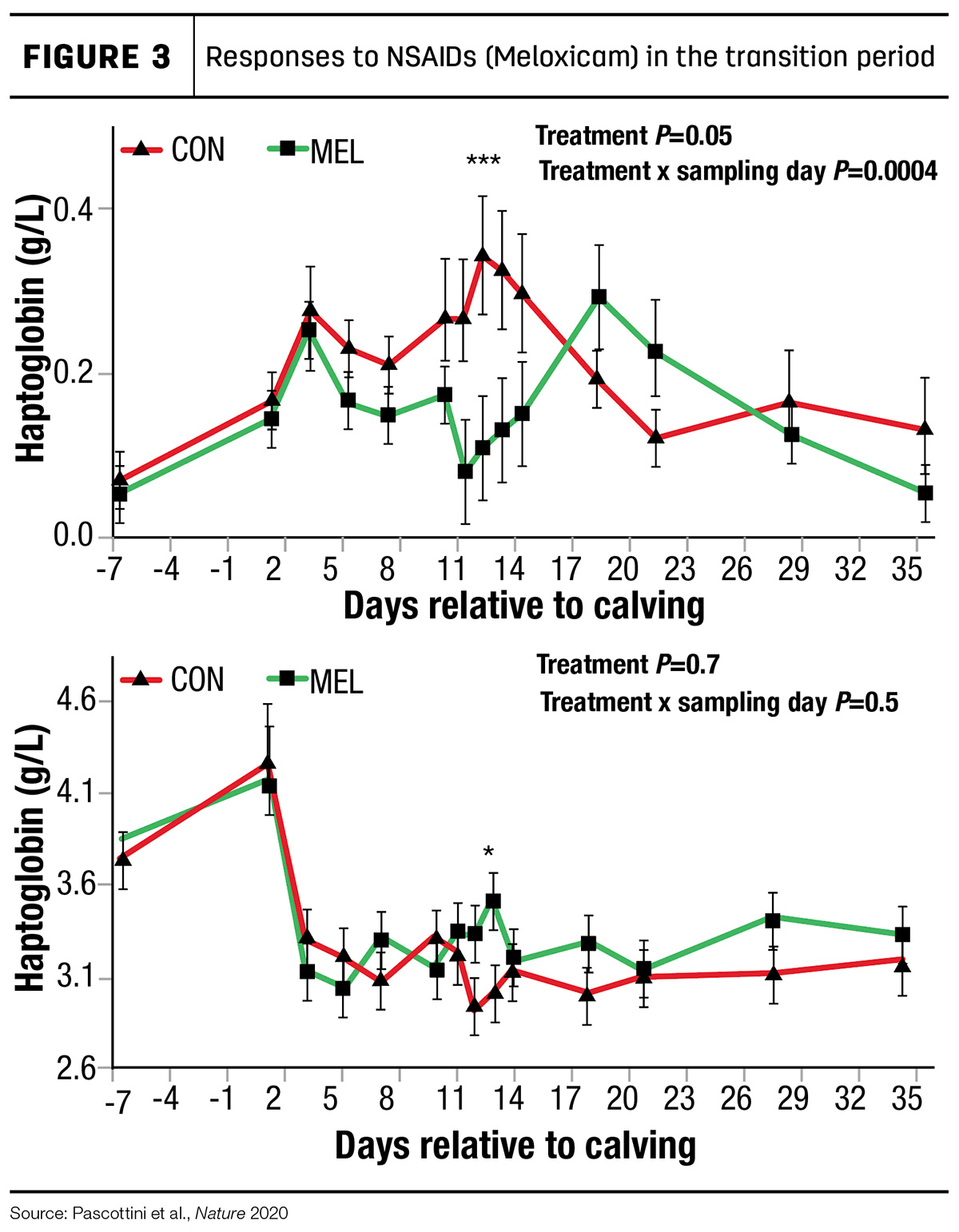

Beyond basic management practices, dairy researchers have been seeking answers to whether this excess inflammation can be treated or nutritionally addressed to improve outcomes, especially during transition. Several papers have been published about the benefit of administering non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as meloxicam, flunixin and aspirin after calving. The results have been varied regarding milk yield and DMI – however, showed positive results regarding various blood metabolites. One recent study reported a reduction in serum haptoglobin levels (a primary means of measuring inflammation in dairy cattle), while glucose was increased (Figure 3). Unfortunately, the practice of administrating NSAIDs has not been approved for use in food animals or for specific conditions.

From a nutrition standpoint, omega-3 fatty acids are on the short list for ways to manage inflammation and prevent chronic inflammation. Fatty acids are primarily fed to dairy cows to increase the energy density of the diet or maintain the energy while reducing the level of fermentable carbohydrate in the diet to reduce the risk of acidosis. The fatty acids primarily fed to provide energy are palmitic, stearic and oleic. In contrast, EPA/DHA omega-3s are essential fatty acids known to be highly anti-inflammatory, aid in resolving inflammation and have a vital role in early embryo development. Research conducted in humans has shown that EPA and DHA are used to synthesize resolvins and protectins, immune molecules that signal the rapid and efficient resolution of inflammation. Studies in dairy cattle have also shown significant milk responses resulting from feeding calcium salts of EPA/DHA, reinforcing the strategy to reduce inflammation and spare more glucose for the mammary gland. Supplementing diets with EPA/DHA may be a more practical way to prevent excessive or chronic inflammation.

Points to remember

- Inflammation is the natural response to an insult, so we don’t want to prevent inflammation from happening. We do want to prevent inflammation from being severe and/or chronic.

- Even healthy cows experience a multitude of inflammatory events from dry-off to calving and throughout their lactation.

- The immune system requires glucose to function, as does the mammary gland. Reducing excess inflammation and preventing chronic inflammation allows more glucose to be funneled to the mammary gland for milk production.

- Best management practices that reduce stress and minimize body condition loss in transition are a great place to start in reducing your herd’s inflammation severity.

- High-producing cows are the result of less stress and less inflammation.